After my suboptimal eyesight dashed my hopes of becoming a pilot, my fallback dream was to become a writer. My teachers praised my writing, but a good teacher encourages anyway; more tellingly, my grades were excellent, which carried more weight. I’ve lived the dream, enjoying a long, successful, and lucrative career as a technical writer. (Even among writers, the percentage of people who’ve made a living at it is very low!) But always in the back of my mind I wanted to write for myself. For the last decade of my working life I joked that someday I would write using adjectives and adverbs, semicolons and dashes. Now, in retirement, I’m free to do so. I want to offer some observations on how the art and science of technical writing compares to the art and craft of fiction writing: what’s the same and what’s different.

At this point in my fiction-writing apprenticeship I estimate I’ve written 200,000 words and at least 20,000 sentences (dialog lowers the average sentence length), but I waited to write this blog post until I could claim credible success writing fiction. I now have a smidgeon. (Yay!) You can find outstanding writers and teachers offering practical advice—successful former tech writers Robert Pirsig, Amy Tan, and Ted Chiang included—with far more experience writing fiction, so don’t weight my opinions heavily. Still, I know the “before” state of the transition as well as anyone.

By the way, some of what I’m passing on I learned from various courses offered by The Great Courses (formerly The Teaching Company). They are college-level courses without tests or homework, and I recommend them all.

What’s the same?

We know about the historical trend from the flowery and ornate prose of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, meant to set a leisurely pace, entertain readers, and show off the writer’s skill, to the short, punchy sentences of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, meant to set a brisk pace, appeal to readers with short attention spans, and remove the writer from the narrative. We have the rise of journalistic style and the disillusionment of World War I, which created Hemingway, Dashiell Hammett, and others, to thank for the transformation, but over the last century the trend has only accelerated. Epistolary novels were invented in the 1600s, but today short stories have been written entirely in tweets.

Today’s fiction is created in a wide range of styles, but editors of commercial fiction push toward the same degree of concision that I was taught as a technical writer. I’m finding that beyond editing out clichés and stereotypes, achieving concision is a slow process of distillation, like turning grapes into brandy. The best sentences emerge from their predecessors, one at a time, sometimes a word at a time, often when I’m not writing. (The worst possible tech writer would be Oscar Wilde, who once said he’d “spent most of the day putting in a comma and the rest of the day taking it out.” I’m not that indolent, but I’m slow.)

At my first technical writing job, the stiff and formal house style was simplified and made more direct over the years. An oft-cited example I remember, the standard introduction to a procedure, was successively honed down one word at a time:

The operator performs the following steps:

The operator performs the following:

The operator performs:

The operator:

You:

In current practice, this procedural signifier is often completely omitted (which I consider going too far). Similarly, at one point at another company we actually wrote steps like “move the mouse cursor to the OK button and click on it,” which today boils down to, “Click OK,” and sometimes is skipped altogether (which again I object to, but whatever).

The common ancestor of both technical writing and fiction writing advice is Strunk & White’s The Elements of Style, which above all counsels writers to “omit needless words.” After saying for years that I was going to write long, lovely sentences using adjectives and adverbs, imagine my chagrin—yes, I say, chagrin!—when the first editing course I took (“Effective Editing“) advised writers to avoid passive voice, lengthy sentences, and adjectives and adverbs and write instead using active voice, vigorous sentences, and precise nouns and strong verbs to indicate action and mood—just what every style guide demanded. For both technical and contemporary, commercial fiction writing, the process is not one of elaboration, but of honing.

For example, in a scene set at a lavish company Christmas party, I wanted to describe what two minor characters wore. I imagined one dressed as a Southern belle with white lace gloves and her date dressed vaguely like Rhett Butler. After I wrote that (always after…), I thought I could do better and searched for images of the famous “Gone With The Wind” character. I saw his billowy scarf and mentioned it. Searching further for a “rhett butler costume,” I hit the exact description: Rhett was a Victorian dandy, and for neckwear he favored ascots. “Ascot” was the exact noun. (In the end, I dropped the whole idea because (a) a Southern belle in her hoop skirt couldn’t fit into a car, (b) they were at a Christmas party, not a costume party, and (c) they were minor characters anyway.) As Twain said (quoting his friend Josh Billings), the precise word is always best.

When writing procedures, technical writers think about breaking down steps into a consistent series of understandable actions. The definition of an “understandable” action has changed over the years. In 1940, when Bell Telephone rolled out rotary phones to replace stick phones, they produced instructional films on how to use them. My career spanned the change of user interfaces from command lines to graphical interfaces. The first Macintosh User’s Guide taught users how to point, click, drag, double-click, and so on, and at one point my employer’s manuals had a standard appendix describing the same thing. Today documentation dispenses with that because tech writers assume everyone knows how to use a mouse, but we’re going through a similar interface change to touchscreen interfaces.

Similarly, in describing fictional action, writers have to decide on the level of atomicity. The standard writing-class example is placing a phone call. If you make the fictional narrative mistake of describing every atomic step of the process, the narrative halts unless the call will trigger a bomb. We understand that fictional characters have bodily functions; unless you want to call attention to some interruption, there’s no need to mention them. For a phone call, “He called his wife and lied that he was working late” is sufficient (and notice how much work “lied” does here). Interestingly, many kids today don’t know how to use a rotary telephone, and why should they? Hey, I don’t grasp features on my smartphone. The bigger the steps, the faster the action: In Galactic Patrol (1937), the next sentence after the new space academy graduate was invited aboard his first command was, “Under the expert tutelage of the designers and builders of the Brittania, Vice Commander Kinnison drove her hither and thither through the tractless wastes of the galaxy.” E. E. “Doc” Smith had a lot to get to, and no time to edit out clichés.

The same thinking that leads to concision in technical writing leads to direct communication of experiences in fiction. In the first example below, the editing advice is to use active voice; in the second, the advice is to remove filtering words:

Ensure that the wing nuts are finger-tight before proceeding.

Tighten the wing nuts by hand.

He looked up and noticed that the sky was blue.

The sky was blue.

Visual media such as film illuminates a whole scene, like the sun illuminates a landscape, allowing the viewer to choose what to focus on. Literature shines a flashlight with a narrow beam: the reader can focus only on what is illuminated by the stream of words you provide. Omit needless words and unnecessary details.

What’s different?

I won’t say I miss deadlines, but “the release is scheduled for Christmas, and your paycheck depends on meeting the date” is compelling; “do I write today or scroll through social media?” is less so. For me, less discipline has meant less focus. Setting time goals (finish a draft by the end of the year) seems to help.

High-quality technical writing is consistent. It’s common to use a controlled vocabulary. Similar items and actions must be described with similar, perhaps identical, language, particularly verbs: computer users click the button, never hit, punch, press, or anything else. (Smartphone users touch it.) However, consistency makes for hack fiction; original expression is rewarded. I’m still searching for the right words, but I no longer worry about writing to an eighth-grade level or restricting myself to a standardized vocabulary. For the sake of variety, if I want a long sentence I write one, and if color is warranted, I color. I seem to write particularly long sentences when listing things; for example, this passage is currently 100 words, 81 of them in the first sentence alone:

She was not going to chance some tiny unknown island pharmacy, so she assembled everything she could imagine needing: [long list of items]. The completed list was her longest ever. It resembled one of her ex’s pharmacy sales orders. Am I compulsive?

Wordle players are familiar with rearranging letters to form words: STALE SLATE STEAL LEAST TALES and so on. English sentences can be constructed in many different ways by rearranging words and clauses. Technical writers are trained to write active-voice, right-branching sentences, but I always used to roll sentences around in my head seeking maximum effect, from left-branching to right-branching, from passive to active voice, and to put the sting of the sentence in the tail, an idea from outside technical writing. Fiction writing is less structured, and now I’m free to structure a sentence any way I see fit. For example, I wrote this sentence: “He walked around the building and saw chaos everywhere.” The sentence is accurate but boring. I wanted to emphasize the chaos—the sting. I rolled the sentence all around, trying different words in different places:

He went all through the building. Everywhere was chaos.

He went all through the building. Everywhere was tumult.

He went all through the building. Everywhere was pandemonium.

He went all through the building, and everywhere he looked, there was chaos.

He went all through the building. There was chaos everywhere.

He went all through the building and saw tumult everywhere.

Your opinions may differ, but I finally went with the boldfaced sentence as the first among equals.

The course “Building Great Sentences” covers cumulative and balanced sentences. A cumulative sentence is built up of clauses or phrases such as “This is the dog that worried the cat that chased the rat that ate the cheese that lay in the house that Jack built.” If you maintain the structure, a cumulative sentence can extend to any length. To show the morning of a stressed-out character behaving abnormally, I wrote:

She left her condo, got into her car, put on her sunglasses, lit a cigarette, cracked the window open, and hit the road.

Basically, a cumulative sentence is what in technical writing would be presented as an ordered or unordered list.

A balanced sentence is constructed in parallel; for example, “Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country” (John F. Kennedy), or “Not that I loved Caesar less, but that I loved Rome more” (Shakespeare). Too many balanced sentences can become singsong, but it’s nice when you can include them.

Technical writers are trained to write colorless, or at best friendly, prose. I never wrote as myself, but as my employer, and ideally, every writer on the team sounded the same. (I acknowledge the authors of the original Unix documentation, who injected subtle humor sometimes imitated, poorly, by engineers when they get punchy.) Fiction writing allows for a chorus of voices: characters, potentially all sounding distinctly different; a narrator; and an authorial voice describing or characterizing action, perhaps even interrupting to directly address the reader. Jay McInerney’s Story of My Life (1988) begins with a vivid first-person narrator’s voice:

I’m like, I don’t believe this shit.

(Trust me, the entire book sounds like that.)

For me, perhaps the greatest difference from technical writing is the unreliable narrator. (No jokes, please!) Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita (1950) is the fictional confessional of a self-admitted pedophile whose account of his compulsive, doomed love for his stepdaughter, who we would today call a tween, is psychologically twisted, morally repugnant, and thoroughly unreliable. One brilliantly telling detail is that the narrator describes tweens that ring his chimes in loving, lavish, and minute detail, while describing those who don’t arouse him, and old women (over 16!), minimally and disparagingly. Lolita brilliantly limns the mind of its main character but, decades of censorship notwithstanding, does not reveal the voice or mind of its author.

A note on Grammarly

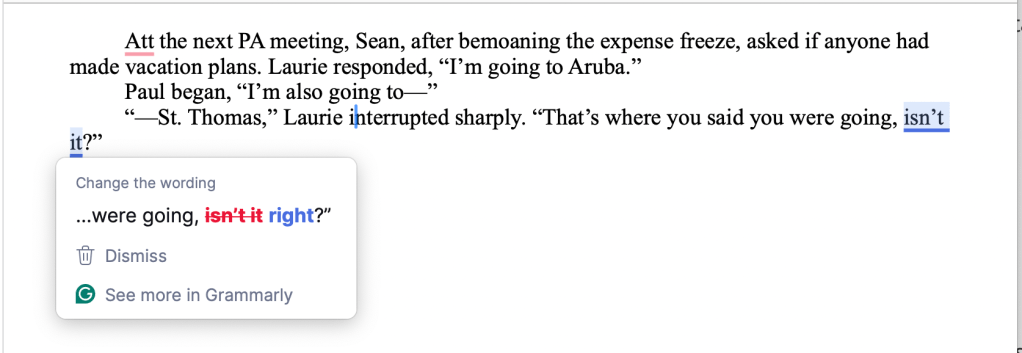

I’ve never been a good typist, and the more heavily I edit my work, the more obvious errors I make. To keep from embarrassing myself I purchased Grammarly Premium. The current Grammarly offers multiple levels of correction and advice. It red-flags grammatical errors, misspelled words, and doubled and missing words, and I’m happy to make those corrections. (I fight with it over my comma usage, which I can improve, but I’m writing fiction and contend that most people don’t speak in Oxford commas.) It also seductively blue-flags passages it thinks can be improved, and here I think about its advice.

Finally, like every current product determined to jam AI down our throats, Grammarly offers AI-based rewrites of sentences and whole paragraphs. Its suggestions tend to make passages static and boring. If I sank to the level of accepting AI rewrites I feel I would no longer be the author of my work.

What do you think?

These are my observations on how fiction writing is, and is not, like technical writing. I may update this post as I learn more. Your comments are welcome!

I’ve been looking for a post like this. I too am a technical writer, close to retirement, with the same ambition.

Just completed my first fiction MS. Despite my excitement, I’m still worrying that my prose won’t be good enough. Oh well. Thank you for writing such a comprehensive piece.

LikeLike